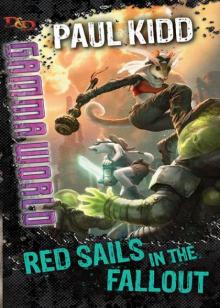

gamma world Red Sails in the Fallout Read online

Page 9

“QED …” Xoota was amazed. “You can do this? You can actually do this?”

“Of course I can. It’s science.” The rat was happier than Xoota had ever seen her. “You see? It’s your ship. You get to captain a ship at last. You get your dream.”

The quoll blinked. “You did this for me?”

“Of course I did. You’re my friend.” The rat stood up, dusting off her hands. “We’ll have to work fast, though. We’ll need you to find us our masts, sails, and parts; take them from anywhere you need to.”

“You’ve got it.” Xoota cleared her throat. “Will there be room for Budgie?”

“Of course. For scouting. And every ship needs a parrot. There’ll be plenty of room.”

Xoota felt an odd emotion. She looked down at her boots. “Shaani … thank you.”

Villagers began levering rubble away from the wall. It would take a lot of manpower to tilt the old moon buggy out of position and back onto its wheels; the thing was more than twice the length of an ancient semi trailer. Thankfully, it was made from a light omega alloy.

It could be done. Still, Shaani seemed concerned. Xoota watched her from the corner of one eye. “What’s the matter?”

“Supplies. We can make the ship; the ship can carry enough water to get us across the desert. But where do we find the water? I’m showing the locals how to make stills, so they can get minimal drinking water while we’re gone. But there’s no way to stockpile the sort of liters we’ll need for the voyage.”

Xoota bit her lip. “How much will we need?”

“Say we have a crew of four. In the heat, each person consumes four liters per day. Now let’s say we average a hundred kilometers a day. That’s a thirty-day trip. That would mean five hundred liters, twice that if we allow for a return trip. That’s a thousand liters.”

The quoll closed her eyes and heaved a sigh. “I know where we can get the water.”

“Really?”

“If we don’t mind making a side trip, a really icky side trip.” Xoota rubbed her eyes. Oh crud. “This is not going to be fun.”

The village square was a churning hive of activity. Shaani presumed upon the enthusiasm of the local residents, racing around and stirring up the workers all in the name of science. Wig-wig raced after her, echoing her enthusiasm. Not surprisingly he was extremely useful for knotting, splicing, and running cables. Shaani ran her hands over the electrical system in the moon buggy wheels. Sparks clicked and flashed from her hands as she felt out the systems, finding the breaks in the circuits. She thieved solder from ancient, ruined machines and reconnected wires. Once the main construction began, all that could normally be seen of Shaani was her backside, legs and tail sticking up out of the hull.

The vessel was going to be impressive. The eight-wheeled chassis stood on wide, sprawling legs, the balloon tires rising higher than a man’s head. Filling the entire village square, the chassis swarmed with people as plywood sheets were screwed in place. Earwigs ran messages, children chased each other between the wheels. The scene was total chaos.

Xoota did the unglamorous job of salvaging parts from the ruins. Among the piles of wrecked shipping, she found sturdy masts and pylons. Sails were more problematic; most had been cut up to make hammocks, water bags, and street awnings. Local weaving technique was not up to anything more complex than woolen blankets and homespun cotton.

It was a problem that caused Xoota a great deal of gloom. She sat at the tent makers, looking through fabrics and feeling a little demoralized. The tent maker, a rather delightful mutant rock wallaby who had a row of electroshock quills down her back and a decided lisp, tried to be as much help as she could. The problem was that local fabrics were made to be light and airy, not wind tight and robust. Most tents were made of wool, cotton sheets, or even woven grass.

The wallaby woman pondered, sparks racing up and down her back. The store had a distinct scent of ozone. “What about old rain jackets? A lot of the old boat wrecks have lots of nylon clothing in them. Old waterproofs?”

“How big an area could we cover?”

“Well, maybe enough for one of the little sails.” The tent maker sat back, kangaroo style, using her tail as a seat.

“Have you found any other old tech cloth?” asked Xoota.

“There are two parachutes, from the old starship’s ejection seats. Those are a godsend.”

“It isn’t enough?”

“Only for the mainsail. This thing’s going to need a lot of fabric.”

Xoota sighed, frustrated. “We still need the top sails, the jibs for the bowsprit thingy, and the … whatever it’s called, the sail for the second mast.” Xoota really needed to find someone who could read and have some of Shaani’s nautical books read to her. That way she might actually understand half of what the rat was talking about. “We need cloth and lots of it.”

“Well, we could get some weaving going. Try and make a much heavier cotton than normal. That might make good sails.”

“How long will that take?”

“A few months.”

“No, we don’t have that much time.” Xoota rubbed at her eyes. The water problem would be critical in a matter of weeks. “What else do people use for big sheets of cloth?”

“Hmm …” The wallaby rubbed her nose. “Leather?”

“Too heavy.”

“What you really need are sharkskins.” The wallaby sighed. “Fat chance of any of those.”

Sand sharks cast off their skins regularly as they grew. Razorbacks salvaged the thin, tough inner membranes and used them to make their huge sunshade tents. But the razorbacks never, ever traded. They merely killed any traveler they could find, ate his flesh, and stole his equipment. Xoota could think of no one who might have captured a tent or accidentally found a pile of discarded sharkskins.

She clambered onto her feet. “I’ll keep thinking. There’ll be something out there.”

“Good luck.”

Xoota was still trying to turn fantasies into practical solutions an hour later. She sat in the shade of the tavern wall, watching the ship being built. Budgie lay at her feet, making happy noises as Xoota carefully groomed his feathers. She was still obsessing about sails when a massive presence suddenly loomed overhead.

The shadow that fell over Xoota was lumpy in a way that simply annoyed her. The quoll gave a sigh. “Hello, Benek.”

“Scout Xoota. Well met.” The colossal human posed with his fists on his hips, surveying the growing shape of the sand ship with a masterful air. “So this is the vessel?”

“It is indeed.”

“The design is surprisingly cunning.” Benek looked the ship up and down. “Taken from old sources, no doubt.”

“No, no, an original design. All Shaani’s work.”

“You surprise me. I had not thought animals capable of such.”

Xoota looked Benek over and wondered what he would look like inside out. “We find ourselves quite capable.”

“And I approve of your efforts.” Benek leaned back on his heels, inspecting the two large masts that had been hauled up into position just an hour before. Braces and rigging made out of home-woven cable were still being winched up into place. “You have gone to great efforts to ensure the success of my expedition.”

“Yes … well …” Xoota’s droll antennae spoke volumes. “Future of your race and all that. Can’t deny the world more humans. After all, look what they did for the place.”

Benek had a backpack sheathed entirely in a pink, translucent membrane. Xoota looked at it in puzzlement then fingered the outer covering. It was tough, light, amazingly strong …

“Benek, what is this? Sharkskin?”

“It is a waterproof covering.” The man was coldly proud of all his fixtures. “The superior intellect prepares for all eventualities.”

The quoll’s temper was at its customary low boiling point. “I don’t need to know why you got it. I just need to know where you got it.”

Benek arrogantly smoothe

d his golden hair. “I bought it from a half-human herdsman. It’s an off-cut. The creature found it in the desert.” Benek brushed his piece of sharkskin clean. “Apparently his clan of scavengers often find old razorback castoffs. They seem to know where to look.”

“They do, do they?” Xoota stood. “Do tell, where can I find this herdsman of yours?”

Half an hour later, Xoota wandered back toward the ship, towing Budgie behind her. Shaani was down beneath the hull, licking the end of a copper wire to see if there was any electrical current. She made a spark on the tip of her tongue and touched it to the wire. Her homemade voltmeter gave her a reading she felt happy with. Grease-stained and gleeful, the rat looked up at Xoota.

“Xoota, old thing. Had some successes with supplies?”

“I have. I have. I’ve found us sailcloth at last.” Xoota spotted a box and sat down. Budgie sat down beside her, apparently quite satisfied with his life. Xoota used him as a backrest. “There’s a local leather—thin, light, immensely tough, waterproof. It doesn’t stretch or shrink with the cold or sun. And it is available in bulk.”

“Sterling stuff.” The rat was overjoyed. “Can we get hold of a sufficient quantity?”

“I think we can secure all that we’ll need.” Xoota steepled her fingertips, her antennae making sly little motions above her skull. “How would you feel about taking a jaunt into the desert?”

“Oh. Tonight?”

“Mmm, starting this afternoon. We need to cover fifty K by tomorrow midday.”

“Midday?” The rat wasn’t really paying attention. She was sorting through a box of rusty screws and bolts salvaged from a dozen different wrecks. “If you like.”

“Good.” Xoota wriggled her toes. “By the way, how go the mutations? No amusing alphas today?”

“No, no. I do feel a tad spry, though. Might be a burst of extra speed in reserve here somewhere.”

“Oh, good.” The quoll plumped up Budgie like a giant pillow and relaxed. “That ought to come in very useful.”

Two long damned days in the desert later, and Shaani was frying inside her skin. The Big Dry was in full force, with the sun burning pitilessly down upon the sand. Anything with the slightest bit of common sense was deep under cover, looking for cool.

Shaani and Xoota, of course, were traipsing around on the sands and trying not to be burned to a cinder.

The rat sheltered beneath her parasol. Wig-wig clung to her, afraid to burn his little feet on the sands. Both women wore thick oversoles of woven dry grass to insulate their boot soles from the sizzling-hot sands. The air shimmered with silver curtains of mirage, and the steady wind sucked moisture right out of the skin. Walking awkwardly in his grass overshoes, Budgie waved his little wings and wilted in the sun.

The two days’ travel saw them far past the belt of huts and shelters used by herdsmen in the winter. The watering holes were drying up in the outer desert, and the razorbacks were closing in on the southern settlements. They moved at night in scattered groups, using secret water caches they had planted months before. By day, they spread out their slick, shiny tents of sand-shark skin and slept through the desert heat.

Hidden behind the crest of a sand dune, Xoota used her binoculars to carefully inspect a distant encampment. There were four or five huge, broad awnings sheltering a dark mass of razorbacks and their riding cockatoos. It was a band of forty, maybe fifty war pigs. They had a krunch wagon parked beside the biggest tent, a balloon-tired cart designed to be dragged along behind a team of cockatoos. A rough-and-ready ballista had been mounted on the cart, but the guards and operators had all fled beneath the awnings. Only the cockatoos seemed to be awake, grumbling and croaking in the heat.

Benek strode up behind Xoota, gazing at the razorback tribe. “Excellent. The mutant scum are at our mercy.”

Xoota didn’t bother looking at him. She was examining the enemy camp. “Benek, go put a hat on. You’ll fry your brain.”

“My neural pathways are not like those of other men.”

“We noticed.” Xoota lowered her binoculars. She spoke for the benefit of Shaani and Wig-wig. “I make it three squadrons, plus what looks like a chief and some sows. One krunch wagon with a ballista.”

Shaani walked awkwardly over the sand, wincing at the heat radiating up from the ground. “Do they have sentries?”

“Nope. They’re not that organized. But the cockatoos will raise the alarm the instant they sense anything.” The quoll tested with her antennae, looking for clear images of dangerous futures, but everything was all a-jangle. “If we can approach downwind, we should be able to get in close. But what we need to do is make the cockatoos scatter and run. Then the razorbacks can’t come after us.”

Shaani stroked her snout. “A bomb?”

“Yep, throw a bomb. But only after we hitch their tents up to the budgies.”

For the purposes of the expedition, Shaani had been loaned a bright green riding budgerigar. Benek had another one, and each rider also led a pack animal, ready to haul away the loot.

Xoota clambered down the sand dune and hauled herself back into the saddle. She waited for Shaani to find her stirrups and get up onto her own bird then waved the expedition forward, aiming to circle the razorback camp.

“Budgies, yo.”

The column moved out with Xoota at the point, Benek guarding the rear, and Shaani juggling a parasol and telescope in the middle. Wig-wig clung onto Shaani’s budgerigar, making every possible use of the shade.

The sand was hard packed and dotted with sprigs of dead, dry grass. Dense stands of spinifex bush stood dry and dense between the hills of sand. It was good, hard footing, dense and dusty. Here and there a termite mound stood out against the sky. Nothing moved. No predators cross the sky. The ground seemed to tremble with the awful heat.

The temperature was making Shaani dizzy, and her mouth was dry. As Xoota led the way between two dunes, Shaani poured herself a drink. She poured yet more into a bowl, and swarms of large, brown earwigs came gratefully down to drink.

“Thanking rat. Thanking much.”

The expedition made a long, circling route around the razorback camp. The stench of the pigs began to fill the air, a stink thickened up by their noisome riding cockatoos. Xoota motioned the others to absolute silence and edged her bird skillfully up beneath the crest of a rise of sand. She peered just over the crest, carefully spying out the enemy camp.

Yes, the positioning was good.

There were three colossal tents filled with warriors, all tangled in snorting, grunting heaps in the shade of their broad tent awnings. The chief was upwind of his warriors. His tent held nothing but his armor, weapons, and a harem of half a dozen razorback females. The riding cockatoos, all sleeping with their heads down and twitching in aggravation at the heat, were in a tent off to one side.

Some broken brick walls stood a few hundred meters away from Shaani’s rear. She moved quietly over to investigate. There, lying on the dust outside the ruins, was a strange object: a great, egg-shaped thing spun out of some sort of thick, coarse wool. The end was missing, the insides were empty, and the surface was shiny. Shaani dismounted and knelt down to investigate.

The object was radioactive. She could feel its warmth. The rat turned her face toward the nearby ruins and pondered.

Benek joined her.

“What is it? An egg?”

“A pupal casing. Radioactive.”

Xoota rode over.

Shaani held up her find. “Radioactive. Quite hot. Benek, you should probably move back.”

“Are you not affected?”

“Of course not; I’m a scientist.” The white rat turned her face toward the brick walls. She held out her hand, palm first. “Those are radioactive too.”

Xoota looked at the ruins. “Gamma moths?”

“Gamma moths.”

The radiation and electromagnetic pulse given off from moths were enough to turn most people into decorative green ash. It was likely there was an undergrou

nd space where the moths had made a colony. It was not a good place to make loud disturbances. It also limited the options for attacking the camp. Once the action began, the team would have to move and keep moving to escape any moths that took flight and became all touchy.

“How shall we divide the attack?” Benek had a crossbow of far more complex design than Xoota’s, with strings and wheels and pulleys. “The rodent could bomb the tents; then we could slaughter the mutants as they try to recover.”

“Yes, let’s call that ‘discarded option B.’ ” Xoota had no desire to spread mass slaughter on the sands. “We’ll be taking ‘smart-arse mutant option A.’ ” The quoll sketched out her intentions. “Wig-wig, if you can dig out around the tether stakes of the tents there and there.” She pointed. “Just take them until they’re almost ready to pull free. Then Benek and I ride through. Benek, go straight in to the far side of the tents, tie the main guy rope to your saddle bow, and spur the hell out of there and head for town. You take the left tent; I’ll take the right.” The quoll pointed to the cockatoos. “Shaani, your job: smoke candles to give us cover. Then as we snag the tents, you throw a bomb near the cockatoos. We want to chase them out into the desert. Once they scatter, you ride straight on to safety. Do not stop. We are not here to take on the entire razorback nation single-handed. Are we clear?”

Shaani was listening. Wig-wig seemed delighted. Benek was flexing his muscles. Xoota’s antennae jingled with a sudden inkling of disaster.

“Benek, I mean it. Tents now; obey genetic imperative later.”

“Of course.” The man settled a helmet over his long, blond locks. “I have heard your opinions.”

Xoota hated it when he said that. She made an irritable noise and turned away.

Earwigs scissored open their wings and fluttered up into the baking sky. They drifted silently through the air, landing in ones and twos all over the guy ropes of the nearest tents. The insects filtered stealthily down, halting as a pig near the edge of one tent rolled over in the heat and groaned. The beast farted, making the bugs duck and move hastily away.

A Whisper of Wings

A Whisper of Wings Queen of the Demonweb Pits (greyhawk)

Queen of the Demonweb Pits (greyhawk) White Plume Mountain (greyhawk)

White Plume Mountain (greyhawk) Descent into the Depths of the Earth (greyhawk)

Descent into the Depths of the Earth (greyhawk) The Open Road

The Open Road Tails High

Tails High GeneStorm: City in the Sky

GeneStorm: City in the Sky The Council of Blades n-5

The Council of Blades n-5 gamma world Red Sails in the Fallout

gamma world Red Sails in the Fallout